It's a pretty bonkers time to be in Spain.

A few months ago, the Spanish province of Catalonia held a referendum on independence. The people of Catalonia feel that they pay more to the Spanish government than they receive from the Spanish government. Catalonia was, centuries ago, an independent nation, and it still holds dear its own language, culture, and strong collective identity. The Catalonians, they feel that they would be better off as their own nation. At least, some of them do. Many of them do. Most of them do. Hence the referendum.

An exit clause, really, seems to be the true marker of civilization. The ability of a people to say "we do not wish to be part of your organization anymore" and for the organization to say "very well, let us divide up our things and go our own ways" is a beautiful thing. An amicable, or at the least nonviolent, divorce. It is, after all, far better than the alternatives. War. Control. Suppression. Abuse. Brexit, however you may feel about it, is a civilized affair. The European Union, wisely, has an exit clause sewn into its fabric.

Like America, Spain has no exit clause.

So the people of Catalonia walk peacefully to the polls to voice support for their own self-determination. The government of Spain responds by sending the national police in to (a) beat old women who are trying to vote, (b) steal the ballot boxes from the polling stations and close down the polls, and (c) dissolve, and subsequently arrest, the entire Catalonian government. It's an outrageous, headline-grabbing affair.

The votes that were cast are overwhelmingly in favor of independence. Of course these results aren't entirely representative, as those who did not want independence were less likely to recognize the referendum, declared illegal by Spain, in the first place. But still, everyone is disgusted. Many who didn't care much about independence if given the choice have suddenly realized that they never had the choice to begin with. You are part of Spain whether you like it or not. For now and for always. 'Til death do you part from us.

I have pretty simple politics: let people be free. Let them be free to do well and let them be free to make their own mistakes. Outside of Catalonia, Spaniards tell us that the Catalonians have it all wrong. If they leave us, it would be bad for Catalonia. It would be bad for Spain. It would be bad for the Euro and for the European Union.

Yes, sure. It very well might be bad for everyone involved. It might not. But we humans have a long history of controlling other humans "for their own good," and more often for our own good. If Catalonian independence bankrupts Spain and crashes the Euro and spins the European Union into catastrophe, that is highly unfortunate. But not to let a people be free because their freedom would make life more difficult for you: that's not justice. That's oppression.

Anyway, a few thoughts. We pedal through Catalonia and it is awash in yellow ribbons. Small streamers tied to mailboxes and multi-story tapestries billowing off the side of buildings. Free our political prisoners. In America citizens call for their politicians to be locked up. Here they hang yellow to bring their parliament home.

Because the parliament is, indeed, in exile. Those that weren't arrested and imprisoned for organizing a peaceful referendum fled to Belgium, and will surely be thrown in jail if they return. This isn't a fringe affair in Catalonia; this is the story. We pass through towns with the faces of the jailed painted on walls. Enormous ¡Si! flags (yes, for independence) hang from balconies. These people don't have a parliament. It's been stolen from them. We find ourselves in the Occupied State of Catalonia, and it's a very strange place to be.

We spend a lot of time thinking about this as we head northeast from Barcelona. It comes up often in our interactions with people, and we have a lot of time to think. For the first time in months, we have nowhere to be. No date or place of arrival. We are deeply flexible, and free to move as slowly as we wish.

More or less. We have but two constraints. The first is that we must not exceed ninety days in the European Union's Schengen Area. That is (having already spent over thirty days in Spain) we must pass through the rest of Spain, France, Monaco, Italy, and Slovenia in our remaining sixty-day allowance. That's not a ton of time, but it should be enough.

Our second constraint is weather. Though it is ridiculously warm at the moment (I'm wearing shorts and a t-shirt), the Pyrenees to our left are blanketed in snow. Most of Europe is blanketed in snow. Much as we'd like to meander the Alps and visit the Netherlands and explore the Eurovelo long-distance bicycle routes slicing across Germany and Switzerland, we cannot steer very far from the coast. The Mediterranean shoreline is the warmest place on the continent, and even a few kilometers inland temperatures begin to plummet. We need to hug the coast. A close, unrelenting bear hug.

So, we take the coastal road. We stay with Pep and Nuria and their kids, Warmshowers hosts in Sant Pol, large ¡Independencia! banners tacked to their windows. They tell us about some beautiful riding ahead, and we enjoy some gorgeous kilometers along coastal cliffs before the road gets too steep and rocky. We turn inland just a little and wild camp in a dense Mediterranean forest. We camp for the first time in over a week, and it's warm enough for us to sleep without both jackets on.

***

Back in Chefchaouen, the Blue Pearl and Hashish Capital of Morocco, we met a few fellow travelers. By now, they're all back home. Or wherever home is at the moment.

Yulin is from China, but when we met him in a a crowded little restaurant inside the azure medina, he was studying for a semester in Girona, Spain. He told us he'd be wrapping up his studies in January and heading to Germany for the remainder of his graduate coursework by the end of the month. But, he said, drop us a line if we make it to Girona before he leaves.

It is almost the end of January, and Yulin has not yet left. All roads to France this side of the Pyrenees pass through Girona, and we agree to stay for a night or two if it's okay with him.

We end up staying four days. Yulin completes his last final exam a few hours after we arrive, and we spend the rest of the week exploring Girona's beautiful old town and celebrating the end of the semester with him and his friends. They're all part of Erasmus, a European student-exchange program, and so it's a diverse group of students from every corner of Europe and beyond. We feel, relatively, a little old, because we are, relatively, a little old. But Yulin and his friends are tons of fun and don't seem to mind a pair of Americans pushing thirty tagging along.

We enjoy delicious Chinese meals in Yulin's kitchen. We enjoy delicious Romanian meals in the kitchen of Yulin's Romanian friends. We crash an Erasmus dance workshop with twenty-something twenty-somethings and learn a handful of Italian and Hungarian dance moves. We stay up late and give away our age when we say at 2AM that we really must be heading to bed. We head to an outdoors store on the edge of town and replace the stolen rear bike lights we've been meaning to replace for the past four or five countries. Yulin is a fantastic host, and it's yet another sad goodbye when we finally depart.

We ride for Figueres. We couchsurf with a friendly guy named Chris. We ascend the shallower end of the Pyrenees. It's a beautiful ride. We reach a pass, about four hundred meters up in the foothills, and look behind us. There is Spain.

We look ahead of us, toward the glinting Mediterranean in the distance. There is France.

Hasta luego.

Et bonjour.

***

We do not speak French.

We do not speak any French.

France is the first country we've been on this trip where we have no command of the primary language. Back in southern Africa, English is common. Maybe not in the villages, maybe not by most of the villagers, but some people know a little. We got by. In Tanzania, it was Swahili. So I learned some Swahili. Not enough to carry on a brilliant conversation, but enough to buy produce in the market and ask for water. Enough to get by.

In Morocco, of course, Lauren astounded all with the Arabic she pulled out of some deep chest she'd been hiding it in for the past decade. And in Spain, we managed just fine. I didn't feel the need to footnote every last conversation these last five or six posts, but most of them were completely in Spanish. Usually Lauren speaking and me listening and nodding along and saying sí, claro as though I'm fully up to speed. We got by just fine.

And now we are in France, and I've suddenly realized that I don't know how to say anything.

I actually realized this thirty kilometers back, over on the Spanish side of the Pyrenees. We'd stopped for lunch and I quickly downloaded a handful of French-for-beginners podcasts. I put one on as we resumed cycling into the mountains. And when the podcast host would request a repeat-after-me, I'd shout loud French into the silent abyss, startling the gophers and sending the birds into frenetic flight.

Bon jour!

Bon soir!

Bonne nuit!

"Good," the patient instructor would whisper into my earbuds. "Now be very sure to get the accent right."

Merci.

Meh-ci.

Mehhh-ci!

***

Tent in French is just tente, so at least that's easy enough. We camp in our tente.

We return to the Mediterranean and ride for days. This section of the French coast is flat and marshy, and it's easy (albeit windy) riding. We cycle along quiet canals and tranquil deltas with thousands of flamingoes—flamingoes!—parading about in the salty waters. We ride by towering water slides and compact theme parks, clustered like villages along the roadside. They are, evidently, a huge attraction in summer, but like the resort towns of coastal Spain, they are shuttered and deserted here in late January. Roller coaster tracks, folding up like Transformers. Ferris wheels, listing idly in the breeze.

We keep well off the main roads. France, we discover, has a great many roads, narrow and veiny and branching off into a frayed fistful of capillaries, narrower still. It makes for fun riding, because these forgotten carriageways and nature trails are virtually car-free, but it also makes for slow riding, because they're bumpy and rutted and go unpredictably off-course every few kilometers.

We use our maps a lot. Back in Africa, in a place like Zambia or Botswana, we'd turn onto one road and pedal seven hundred kilometers in one direction. We'd spend a week or more on that same road, veering off only to camp or resupply. No turns. No getting lost. No stoplights, even.

In France, we are constantly getting lost. We do not remain on any one road for more than a few thousand meters at a time. A bike path begins and soon it mutates into a boardwalk and a little later it becomes a muddy tractor path and then suddenly it's a busy national road, but only for thirty seconds before it once again peels off into the countryside and transforms into a hiking trail. Yield signs and traffic lights everywhere. We stop often.

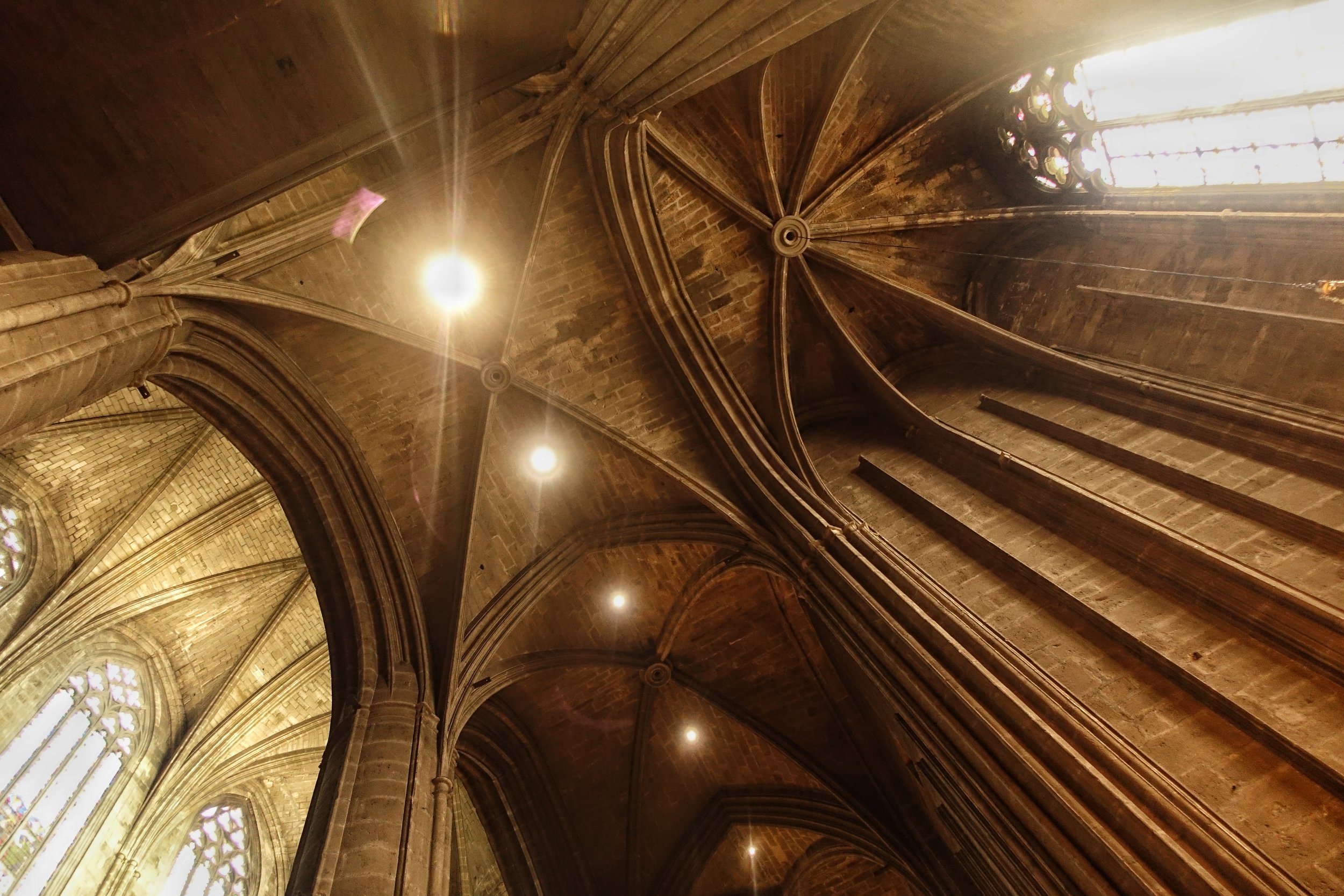

We spend a few days in Narbonne with our Couchsurfing host Gael. We roam the town and explore the churches and cook big meals for the three of us. We pick up a cheap bottle of wine to accompany dinner, then feign offense when Gael reads the label, puts the bottle back on the table, and pulls out his own, suggesting we all might like it better. The French can be very particular about their wines.

We reach Montpellier. We stay six nights. We surf a few different couches and spare bedrooms. We meet some really wonderful people, cook dinners for and with our hosts, and do our best to stay out of the rain. Montpellier, all of southern France really, is getting a lot of rain.

***

As the clouds dump buckets on the city, a different kind of storm is brewing deep in Lauren's ear canal. Our health has improved markedly since last month in Jaén—our pinkeye and coughs are long gone—but this past week or two Lauren has been feeling a little under the weather. Sniffles and congestion, sure, but most pressingly a big clump of ear wax that has hardened in each ear. I peer in with my headlamp and it is not a pretty sight. Like the boulder in Indiana Jones lodged deep in an underground Peruvian tunnel. To spare you the graphic details, it is disgusting.

Disgusting, and painful, and worsening. During our week in Montpellier Lauren goes from having difficulty hearing in her right ear to being functionally deaf in her right ear. The boulder has moved deeper into the tunnel, and as we set off from Montpellier the next morning, it comes to a resting place against her eardrum.

It is stuck, and it is stuck well.